Where I live, it gets hot in the summer.

Very hot.

And when the summer sun bakes the Arizona deserts, that hot, light air rises high above the saguaro and the creosote, above the Catalinas and the Superstitions, and births a low pressure system that sucks wind from south. With that wind comes moisture from the Gulf of California and the Pacific Ocean.

And with that moisture come the Monsoons.

When they come they come with a flair, with dramatic skies full of roaring thunder and spears of fire. But there are summers – too many of late – when they hardly come at all, and then the land stays brown and the air stays surly.

This year, though, the rains came. They came with a robust and rip-roaring vivacity, filling the streams, greening the desert mountains, and growing the flowers.

And when you have flowers, you’re bound to have butterflies.

I seem to see them everywhere this summer. When I look out my window they are there, bobbing through the air like blown leaves. When I walk in my yard, or in the neighborhood, they are there, the Red Admirals and Painted Ladies, the Black Swallowtails and the Cloudless Sulphurs, fluttering from blossom to blossom, impatient, determined, so exuberantly colored they are like flowers themselves.

Flying flowers.

They are there, and it seems they have always been, always dappling the skies and the summer days with their grace and beauty.

They are in the poems and stories of old, and in the paintings of the Old Masters. They are in the tropical forests and the temperate forests, in the Himalayan Mountains and the Rocky Mountains.

They are in the Australian Outback and the Arctic tundra, in city parks and country fields and your own backyard.

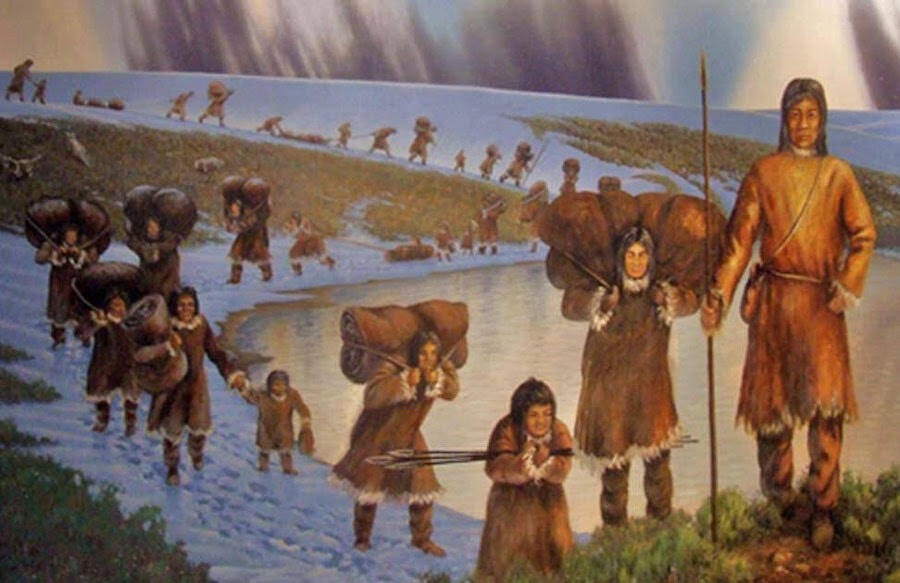

When the seafaring explorers set foot in a new world, butterflies were there. When the earliest Americans traversed the Bering Land Bridge, or made their way down the coastal “Kelp Highway” 20,000 years ago and beheld a strange and vast new land, butterflies were there.

When our distant ancestors climbed down from the trees some two million years ago, and set forth on the African savanna, butterflies were there.

Butterflies, it seems, have always been “there”.

But they haven’t.

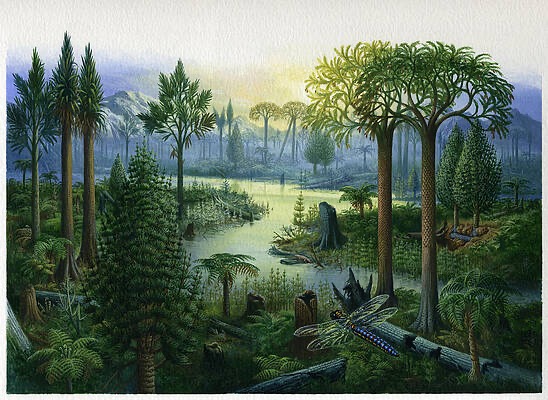

Imagine a distant world, a world so strange and distant that there are no birds, no mammals, no flowers at all. A strange and swampy and relentlessly green world, where queer, Seussian trees fill the horizon, and dragonflies with two-foot wingspans prowl the air.

A world where you could walk from California to Australia.

Imagine a stream flowing through this long-ago land, and one day, a small, Caddis fly-like insect crawls up the muddy bank and sets up housekeeping amongst the mosses and ferns.

It’s a daring endeavor, fraught with peril. But the reward would be immense – a life free of the water, free to find and exploit new food sources, free to fly throughout the giant continent we call Pangea.

It’s a daring endeavor, but it suceeded. And so, some 300 million years ago, the moth came to be.

When they first evolved, these pioneering moths had jaws equipped for chewing, like the caterpillars of their youthful days. But after awhile – say, 60 million years of “while”, and about the same time that dinosaurs made their debut on the planetary stage – moths developed the coiled, straw-like mouthpart, called proboscis, capable of sucking up water, and, more importantly, sap from the early conifers that dominated the Carboniferous landscape.

In the movie “Field of Dreams, Iowa farmer Ray Kinsella hears a persistent voice whispering “If you build it, they will come”. He does build it (a baseball field), and they do indeed come (the 1919 Chicago White Sox). In the natural world, that same mantra is one of the guiding principles of evolution; when something new arrives on the scene, it creates new opportunities for adaptation, and “they” (new forms of life) invariably follow.

One hundred and thirty million years ago, the plant world built something astonishingly new.

It built…..the flower.

Before this, the Bryophytes (mosses), Pteridophytes (ferns and horsetails), and Gymnosperms (conifers) were dependent upon the vagaries of the wind to disperse their spores and seeds, but the Angiosperms (flowering plants) had a better idea – convince the insects to help fertilize the seed, and, once fertilized, enlist the aid of birds and mammals in dispersing it by encasing the seed in a protective and tasty fruit.

Nectar was the ambrosia flowering plants devised to entice flying insects to visit their blossoms, and before long bees – a very efficient pollinator – evolved from a predatory wasp. But there was another flying insect already equipped to take advantage of this new food source. Having a straw for a tongue meant that moths could effortlessly move from sipping sap to sipping nectar, and that’s exactly what they did.

But moths – then, as now – were mostly creatures of the night, and many flowers, especially where the nights are cold and damp, close at night and open in the morning. If you are a moth , and you are loath to miss out on this daytime floral feast, what can you do?

Simple. You become a butterfly.

” If you build it, they will come”.

As lepidopterists love to point out, a butterfly is really just a moth that is active during the day….but a very different kind of moth. Color is irrelevant to a night flier, so a moth’s wings are a drab affair. And because feeding and breeding (and staying alive long enough to do both) are a moth’s only goals in life, moths long ago evolved rudimentary “ears” to detect predators and, in some species, to hear the ultrasonic mating call the male sends out. Many moths (and butterflies) also dab themselves in a chemical “perfume” called pheromone to attract a mate.

But because the day is awash in light, color is vey relevant indeed to a day flier, and soon after the first butterflies appeared – some 98 million years ago – their wings became the dazzling palette of color and design we delight in today.

Butterflies, though, didn’t evolve their beautiful wings for our benefit. Because color matters in a sunlit world, when moths became day fliers they painted their wings with vivid colors to broadcast their species, gender and allure to a potential mate. After all, in a world a’flutter with 17,500 different species of butterflies, it helps to recognize a suitable suitor when you see him (or her).

Those spectacular wings have other purposes, too. Bright and wondrous wings can help a butterfly recognize its own species, but they can also attract a predator’s attention, and butterflies have more than a passing interest in survival. What to do?

Well, suppose you could – when danger is near – just make those colors disappear? A pretty nifty solution to the problem, right? As it happens, that’s exactly what the butterfly did. Over time, through natural selection, the underside of its wings evolved into a rather humdrum affair, cast in muted, “earthy” colors. When a butterfly senses peril, it will fold its wings together and – like Harry Potter beneath his Cloak of Invisibility – simply disappear into the background.

Mimicry is another defensive ploy in a butterfly’s bag of tricks. Some butterflies – and moths as well – have evolved illusory “eyes” on either the top or bottom of their wings to frighten predators away….or startle them long enough to allow for a quick getaway. The Owl butterfly, for example, has decorated the underside of its wings with large, owl-like eyes guaranteed to give any bird second thoughts about attacking it.

Another bit of morphological subterfuge in the butterfly bag of tricks is the “false head”. Since birds tend to attack a butterfly’s head first, some species – such as the Common Tit pictured below – have evolved pseudo antenna on their tails to deceive a bird into striking there, following the principle that losing part of your wing is better than losing your head.

But it’s not just counterfeit eyes and false heads that can help a butterfly win the survival game.

During its caterpillar days the Monarch, that renown migrant that flies as much as 3,000 miles to reach its wintering grounds in Mexico, regularly dines on the poisonous milkweed plant. This not only dissuades predators from eating the caterpillars, but the adult butterflies as well, since it still has the toxins in its tissues.

The Monarch, though, is not the only butterfly to have learned that a little toxin in the tissues can help it win the survival game. Viceroy caterpillars chow down on bitter willow and poplar leaves, which saturates their bodies with bitter salicylic acid – the same compound that teens everywhere use to combat their acne. The Viceroy butterflies inherit this toxicity, and birds, who don’t get acne, learn to look elsewhere for a tasty snack.

But of course, for a bird to learn that a certain kind of butterfly tastes less than enthralling it has to sample a good many butterflies, which is a bit discouraging if you happen to be one of the butterflies sampled. So once again, mimicry has come to the rescue with what might be termed the “look-alike ploy”. By themselves, the colors and patterns of their wings would eventually have a protective effect, but that effect is enhanced when the two species look similar to each other, since less butterflies of either species need be sacrificed to the bird’s learning curve.

I rise from my desk and step outside. A late summer breeze stirs the air, and I inhale deeply. It’s good to be alive on a day like this. Alive to look and feel and listen. Alive to the warmth of the sun, to the sound of the leaves dancing in the trees, to the sight of the birds and the bees and……yes, to the butterflies. They are still here, floating from one flower to another, sipping the nectar, pollinating the plants, and spreading their spectacular wings just as their kind have done for many millions of years.

One alights near me, a cloudless sulphur, and for just a moment I want to believe that it’s the same Phoebis sennae that I saw last month, and the month before that, and maybe even last summer. But I know that’s not likely.

A butterfly’s life, like that of nearly every insect, is a fleeting thing, a swirling ember that flares brightly for a moment and then dies. Most butterflies live only two to four weeks, including the sulphur I stood admiring. They fill the skies throughout the spring and summer because the eggs that were laid the year before were laid at different times by different butterflies, beginning the cycle from egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly at staggered intervals. This means that for every butterfly that dies on a certain day, another is likely spreading its wings and flying for the first time.

Fleeting lives. As a ranger at the Grand Canyon, I once gave an evening program I called “The Grand Giftshop”. The idea behind it was that nearly every visitor to a national park – especially a park as celebrated and iconic as the Canyon – likes to bring a souvenir or two home as a memento of their visit; I certainly do. But I suggested that there are other souvenirs, perhaps better souvenirs, that they could carry away with them than t-shirts, photographs, and paperweights.

One of these I termed The Joy of Being Human.

By this I meant that, as human beings, we had the special privilege not only of living without a constant fear of being eaten, or of finding enough to eat, but of having a brain complex enough to marvel at the intricate mysteries of creation. To be able to write music, to read books, to gaze at the walls of a mile-deep canyon and trace the outlines of the immense journey life had undertaken from a trillion yesterdays to the spectacular now.

And, I might add, to have the time to do it in.

The butterfly I was watching would never know how fleeting its days really are. Or how much beauty its painted wings – and the painted flowers those wings make possible – would grace a summer’s day. But I did. And as I walked back into the house, I thought of this line from the poet Christina Ward:

“I do not want this world without butterflies. I could not bear the wailing of the flowers.”