The rain flew like bullets, cratering the sandy soil as we cowered beneath the wind-tossed tamarisk. The lightning flared and, right on its white-hot heels, the thunder exploded. Our boats, three small inflatable kayaks that we had dragged ashore when this summer tempest attacked, shivered in the wind.

We cowered and watched nervously as the day grew older and the storm showed no sign of abating. We had no map, our takeout lay an unknown distance ahead, and we were woefully unprepared to spend a night on the banks of the river.

How had we gotten ourselves into this mess?

* * * * * * *

Some adventures are long and meticulously planned affairs, carefully plotted over the course of weeks and months with maps, and guidebooks, and consultations with others who have gone before them.

And some are as spontaneous as a smile.

Dale and Katy Schmidt, like my wife Sharon and I, were park rangers with a thirst for adventure. Resplendent adventure, in places natural and lovely and wild. And working at the Grand Canyon, in the heart of the spectacular Colorado Plateau, we had lavish opportunity for it. We climbed mountains, rafted rivers, skied snowy trails, and trekked to remote and secret Shangri-Las.

It was the summer of 1986, and we had driven to Hannagan Meadow, in Arizona’s Blue Range Primitive Area, on the eastern edge of the state. We had come to savor some high country splendor. At over 9,000 feet above sea level, the Blue Range offered the chance to ramble through groves of spruce and fir, and to dip our heads into the cool, alpine air.

We arose early on that July morning, consumed a quick breakfast, and set out on the trail. The air was fragrant with the promise of a delectable adventure. Clark’s Nutcrackers and Stellar Jays filled the branches above our heads with a peckish vivacity, and the flower-soaked meadows we discovered filled our hearts with delight. We snacked on wild strawberries, gooseberries, and raspberries as we wandered along.

We lunched in a meadow near “P-Bar Lake” – which is actually a glorified puddle – and then tramped down what we believed was a trail to our destination, Grant’s Creek.

But there was trouble brewing in the sky, and as we struggled down the “trail”, what had begun as a flock of pretty white puffs of cumuli had attached a “nimbus” to their name and grown distinctly more ominous. The sky grew dark and so did our spirits, as we realized we had missed the real trail to Grant’s Creek and were now thrashing hopelessly about in a dense tangle of trees and shrubs in a nameless side canyon.

And then it began to rain.

The rain eventually stopped, as rain invariably does, and – substantially soggier than before – we started. We started following a feeble, little creek that we hoped might carry us back up to T-Bar Lake, but at times the creek itself seemed to disappear. We started looking for blazes – route finding cuts on the trunks of trees – to help us along, and we found a few. We also found bear claw marks on a tree or two.

And then we found a trail.

Maybe THE trail.

But which way to turn? With confusion as our co-pilot we first walked one way, then changed our minds and walked the other, then gave up the trail entirely and set out across the trackless forest looking for the road we believed HAD to be nearby.

And amazingly, we found it.

But which way to turn? Nobody knew, and the trees weren’t talking.

A steady rain began to fall. We had to make a decision, and we did. We turned right.

Three miles later, we realized that right was wrong. By now we were demoralized, exhausted, and very wet. And it was still raining.

Katy knew what to do.

Standing in the middle of the road, she waved her arms frantically at the first car that approached us. It was a young couple in a pickup. She spoke to them.

Three minutes later, we were sitting in the bed of that pickup, heading back to Hannegan Meadow.

* * * *

That night, crowded into the cab-over camper Sharon and I had installed on our small, 1977 Datsun truck, we discussed our options. After a damp and discouraging day, and with more rain expected, no one had any enthusiasm for another ramble in the Blue Range.

“Here’s a thought”, Dale offered. “On our way out, Katy and I noticed that the Puerco was flowing pretty good. No one I know has ever run that river. How about we give it a try?”

“The Peurco?”, I replied. “Where’s the Puerco?”

Dale explained that it was the river that ran through the Petrified Forest and Holbrook, but that it was usually dry. In fact, it was almost always dry. A ghost river. But now, because of all the heavy rains in the high country, it had come back to life.

I thought about it, and the thought of running a river that almost never ran, that very few people had ever attempted, was irresistible. We had brought our inflatable kayaks and gear – just in case – and we had two more off days to spend. It was perfect.

Sharon and Katy must have thought so, too, because soon we were all excitedly looking at a map and plotting our strategy. Come morning we would drive out of the Blue Range and down to the town of Springerville, over to St. John’s, and then across Apache County on Highway 180 to Holbrook, crossing the Little Colorado in the process. It was 134 miles from Hannegan Meadow to Holbrook, so we’d need an early start.

The Holbrook Bridge would be our takeout, so Sharon and I would park our truck near the river, then we would all ferry back in Dale and Katy’s van to the put-in, in Petrified Forest National Park.

On the map, the distance on the Puerco that we’d have to cover looked to be no more than twenty miles. We were experienced river runners; paddling that distance in a day should be no problem.

No problem at all.

* * * *

“You’re joking, right?”

The ranger behind the desk at the Petrified Forest Visitor Center looked from one face to another, searching for the telltale twinkle that would reveal we were pulling his leg.

“No”, Dale assured him, “we really want to run the Puerco. Do we need a permit for it?”

A maintenance ranger who had been standing nearby spoke up. “Heck, I’ve been here two years and I’ve never even seen water in that river. No one runs the Puerco, ’cause the Puerco doesn’t run!”

“Well, it’s running now, and we’d like to try it,” Katy said. “But do we need a permit?”

The ranger behind the desk said he reckoned not, and wished us luck. We thanked him, and turned to go.

“Hey, wait a minute”, the maintenance ranger hollered as we neared the door. “I want to take a picture of you guys.”

We spent a few fascinating minutes exploring the poignant – and petrified – remnants of an ancient forest that covered this area some 225 million years ago, at the very dawn of the Age of Dinosaurs. But this was no time to dawdle. It was already mid-morning, and we had a ghost river to run.

So we climbed into our vehicles and headed to Holbrook.

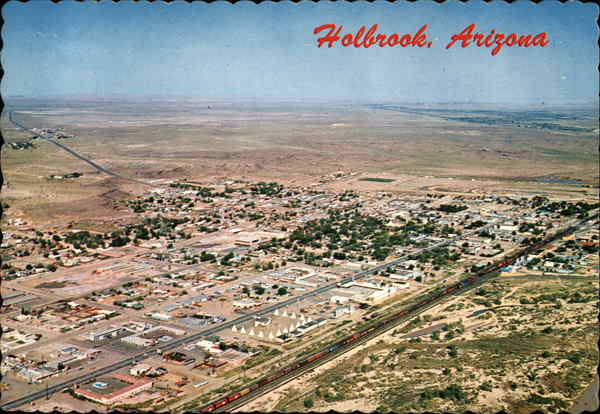

Like most towns in the Southwest, it’s easy to know when you reach Holbrook. The town simply appears, with scarcely little prelude, out of a seemingly endless sea of high desert scrub.

Route 66, the “Mother Road” of America, runs through Holbrook, and its chief claim to fame is as the “Gateway To The Petrified Forest”, although the chance to sleep in a tepee also ranks as a prominent feature.

But sleeping in a tepee was not on the agenda as we rolled through the town. Making sure we had a vehicle waiting for us when we paddled into Holbrook later that day was, and so we quickly found the bridge, parked the camper, and drove the van back to our put-in in the Petrified Forest.

It was time to launch on the Puerco River.

But first, a little background.

Rivers – especially rivers with water in them – are a big deal in Arizona. People notice them. And the Little Colorado River is no exception.

The Little Colorado rises as a clear mountain stream in the White Mountains, in mid-eastern Arizona, and flows for 340 miles until it meets the Colorado, at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Or doesn’t. Flow, that is. Like many other waterways in an arid state, the “LC”, as river runners tend to call it, is perennial over only a portion of its course. Between St. Johns and Cameron, most of the river is a wide, braided wash. Between Cameron and the Colorado, nourished by springs and rainfall on the Kaibab Plateau and encouraged by a geologic uplift, it has gouged out a truly spectacular canyon 3,000 feet.

The LC’s major tributry – the Puerco – did not have a Kaibab Plateau to nourish it and carve through. It begins -when it begins at all – in the lightly-watered sagebrush and scrub forest country near Gallup, New Mexico, and weaves its dusty way 167 miles across the high desert until, joining the Little Colorado, it ends in Holbrook.

Which, as we shoved off into the river that morning, is exactly where we intended to end our journey.

* * * * *

“Puerco” means pig in Spanish. But, like many words, it has more than one meaning, and we had scarcely shoved off and began paddling before we fully understood why the early Spanish explorers in this region had called this river the Rio Puerco; it can also mean “dirty”.

Dirty as in silt. Dirty as in mud.

It is said that the miners and the pioneering river runners in the Grand Canyon had an ongoing joke about the water in the Colorado River. There was so much mud in the water, they would insist, that it was “too thin to plow, and too thick to drink”. (This was before the completion of Glen Canyon Dam, in 1963, began to trap most of that sediment in Lake Powell).

Well, if that were true of the Colorado, then it was also true of the Puerco. In spades.

Dale and Katy, who each had their own inflatable kayak, launched first. Sharon and I, who were sharing our bright orange Sea Eagle, brought up the rear. It took only a few strokes for us to notice that our orange kayak was becoming freckled with mud drops.

“It’s a good thing we brought along plenty of water”, I remarked. “I don’t think we’ll want to drink from this river!”

But we did want to run it. One of the undeniable hazards of floating a ghost river is that the meteorological magic that brought it back to life might just as readily return it to the grave, that the water will simply run out before you finish your trip, leaving you high and dry and miles from the nearest road.

We had talked about this unpleasant possibility the night before, and had decided that we would make our final decision just before we launched. If the water was perceptively dropping, if it was channeling between islands of mud, then we would abandon our impetuous scheme and examine the stony cadavers of long-dead trees.

But that’s not what we saw. What we saw was a robust and muddy river filling its banks and showing no sign of impending death.

What we saw….. was an invitation to adventure.

Commitment can be a beautiful thing, a moment when all the doubts and fears fall away and you are swept up in the shining now, in the current of come what may. You’ve done what you can, you’ve plotted and planned and prepared, you’ve given a wish it’s wings, and now it’s time to fly.

That’s how we felt as we pushed off into the flow of this mysterious river. Committed. Our impulsive, diaphanous dream had come true.

We were floating down the Puerco.

As I suggested above, we were not new at this. We were chronic river rats, and we had adventured on many of the West’s premier whitewater rivers. But this was different. On those we had been guided by guidebooks, alerting us to the rapids and holes and other potential riparian hazards that lay ahead.

This would be different. On this river, we would have no help at all.

For the first few minutes the Puerco was flat and coppery in the noonday sun, and we drifted swiftly along savoring the feeling of doing something that few others had done. We were pioneers! But then, seemingly out of nowhere, a herd of four-foot waves reared up and nearly flipped us.

Our ghost river was haunted by phantom waves.

We knew what they were. Sand Waves. We had encountered this breed of water sprites before, most notably on the San Juan, just north of Monument Valley in southern Utah. They dwell where swift and shallow rivers flow across a sandy bed. The current shifts the sand just enough to create a wave, and that wave spawns several more, until there is a train of leaping waves where moments before there was only flat water.

Almost as quickly as they are born they die, and when I glanced back shortly after careening through them they were already perishing. Sand waves can be great fun – like a ride on a bucking bronco – but they could also toss you and your gear into the river if you weren’t vigilant.

I decided I would be vigilant from now on.

* * * *

Before long we faced another unexpected challenge. But this one wasn’t going anywhere.

Dale saw it first.

“There’s something across the river. I think it might be a bridge.”

We squinted to see what it might be. From this distance it looked like a massive black log floating sideways down the river. But it wasn’t moving and we were, and very soon we could see that it was no log. It was a bridge, a black paneled railroad bridge, and that bridge looked like trouble.

“I’m not sure we can make it “, Katy yelled back at us. “There’s hardly any space to get through!”

The river was high and the bridge was low, a very unsettling combination when you’re floating towards it. We might be able to portage around it, but that option was quickly disappearing as the swift river hurried us ever closer.

“I think we can do it”, Dale hollered. “Just lie backwards and make yourself small!”

Dale was the most experienced river runner in the group – it was he who had introduced Sharon and I to the sport three years earlier – and so we trusted his judgement and lay backwards in our Sea Eagle. It was strange and it was unnerving, blindly hurtling towards a steel wall while lying flat on your back. The danger was twofold; we could pile up against the bridge and be thrown into the river as the water surged into our craft, or, much worse, we could be wedged tightly beneath the bridge, unable to escape.

Light, darkness, and then light again. We slid under the bridge with scant inches to spare, but we made it. We were through! With whoops of joy and relief we floated on.

There would be two more bridges just like this one to squeeze under in the next few miles; our final passage even had the added pizzazz of a train rumbling overhead as we floated beneath, its wheels no more than a foot above our heads. But having done one the next two were much easier.

I might even say fun.

And so on we went down our ghost river, dodging sand bars, bouncing through sand waves, and admiring the terrain on either side of us, studded with cottonwoods, willows and tamarisk along the banks, and sagebrush, saltbush, and widely-scattered juniper trees farther back.

And seeping through it all was a sweet, lustrous solitude.

* * * *

It had been sunny and hot when we had launched, and the sand waves felt cool and refreshing when they splashed over us. But for some time now we had been casting uneasy glances skyward. Baleful black clouds, cloudburst clouds, had been slowly gathering above us, and a downdraft had begun to ripple the water.

It was summer in the Southwest, and our years at the Grand Canyon had taught us that once the summer monsoons had arrived, any given afternoon could be riven by a sudden thunderstorm.

And this was definitely one of those afternoons.

The storm started with a few fat drops riding the downdraft, and then, quicker than we could say “head for shore!”, the celestial dam burst and the deluge began. Heads down against the onslaught, we paddled hard for the river’s edge.

Dragging our kayaks onto the bank, we found shelter beneath a large, feathery tamarisk. It wasn’t much, but in this open country it was better than nothing.

And this was a big one. The sky grew darker still, the wind blew frantically, the rain flew ferociously, and the land trembled with blasts of thunder.

How long would it last?

We had more than a passing interest in its duration. It was late afternoon now. And, as I said at the beginning of this narrative, “we had no map, our takeout lay an unknown distance ahead, and we were woefully unprepared to spend a night on the banks of the river.” As in, very little food, very little clothing, and no shelter at all.

An hour later, it’s fury spent, the storm dissolved into memory. Four soggy river rats crept out from beneath their make- believe shelter and climbed back into their boats.

“Well, at least we won’t have to worry about the river running out of water now”, I cracked.

The sun was dismally low on the horizon. We begin to paddle, to paddle as if time was running out, which it was. We saw and bounced through more sand waves. We saw and veered through an actual rapid, nearly hitting a large rock. We even saw three wild horses grazing on the bank.

What we didn’t see, though, is what we most wanted to see – the outskirts of Holbrook, Arizona.

* * * * *

And so the night caught us, and we had to bivouac.

Glumly pulling our kayaks up onto a small beach, we took stock of our supplies. Luckily, Sharon and I had dry shirts and pants to change into; unluckily, Dale and Katy had no dry clothes at all.

We had one can of tuna fish, a few crackers left over from lunch, and a little beef jerky. We had our ponchos, a first aid kit, and one thin, emergency space blanket. And that was it. We were so certain this would be a simple, one day trip we didn’t bother to bring anything else.

Sharon found a few matches in our first aid kit, and Dale – with a liberal dose of cleaning fluid from his patch kit – managed to get a small fire going. We could still see flashes of lightning in the distance, and as we sat around the fire and shared our meager meal, we shared reflections on our day as well, and watched a full moon slowly rise above the river.

And then I saw something I had never seen before.

There was an imposing butte behind us, to the north and no more than a quarter mile away. In the moonlight it looked vast and mysterious, like some ancient edifice suffused with secrets. But it must have been suffused with rain as well, because directly above it, shimmering in the night, was a bow built of moonbeams.

It was a moonbow, as white as ivory and as fanciful as a dream. The moon, climbing in the south above a ghost river, had spun a ghostly rainbow and hung it above a phantom butte. It was ravishing.

A moonbow , and we had a front row seat. I had heard of them but never seen one, and now, as we watched it shining so improbably in the night sky, I was suddenly glad that we hadn’t reached Holbrook, after all.

* * * * *

There’s an old joke – I usually picture Groucho Marx saying it – that goes: “There’s nothing like a good night’s sleep……and that was nothing like a good night’s sleep!” I thought of that particular chestnut as I struggled to my feet the next morning. Sharon and I had slept – and I use the word loosely – on a poncho spread out on the cold, hard sand, covered by the foil-thin space blanket. Dale and Katy had slept on their ponchos near the fire , although Dale only fitfully, since he had been up and down all night tending the fire. He had done a fine job, for when we rose at dawn the fire was still burning.

Fortunately, the rain that birthed the moonbow never did reach us. The night had been cool, but dry. Rising, we warmed up by the fire and then – since we had no breakfast to slow us down – shoved off into the Puerco.

But it wasn’t the Puerco for long. Soon it blended fortunes with another occasional river, and we were riding on the back of the Little Colorado. And soon after that – no more than two miles from our impromptu camp – we came upon a bridge.

We pulled ashore. Was it our takeout bridge? The vegetation on the bank was high and dense, not only blocking our view but promising a challenging scramble to reach the road.

Was it our bridge? There was a smaller pipeline bridge just beyond it. In our haste to get back to the Petrified Forest yesterday, we hadn’t really taken a close look at the bridge, but none of us remembered that pipeline bridge.

Had we taken the trouble to climb that bank, this is what we would have seen, with our truck parked just out of sight behind the trees.

But we didn’t see it, because we didn’t climb that bank. “I don’t think this is it”, Dale said. “We’re probably not even in the town yet”, and the rest of us agreed. And so we climbed back into our kayaks, and paddled right past our takeout

And we were having a grand time. With the combined waters of the Puerco and the Little Colorado the sand waves were even bigger than before, and we whooped our way through one exhilarating set after another, while keeping an eye out for the bridge we were sure lay ahead of us.

But the bridge never came, and while wondering just how much farther that elusive town might be, something else happened.

The river disappeared.

* * * * *

Sharon and I were ahead of the others, and we were the first to see it. Downstream, maybe fifty yards in front of us, the river seemed to pool, and then simply vanish into nothingness. It was there, and then it wasn’t. But rivers don’t just abruptly vanish, and I was suddenly very worried.

“Paddle!”, Sharon yelled. “Paddle to shore. Now!”

We paddled. Digging deeply, urgency fueling every stroke, we managed to reach the shore before reaching….whatever it was that was swallowing the river.

Our friends were just now coming around the bend. Seeing us on the shore – and seeing the danger downriver – they quickly joined us.

Together we walked towards the mysterious void. And then it was a mystery no more.

“I think our river trip has ended”, I wryly remarked.

We were standing at the edge of a 20-foot waterfall, with some very nasty hydraulics at the bottom. Water that tumbled over the lip of the fall crashed back on itself after reaching the bottom, creating what river runners call “keeper” waves. If you get caught in a keeper wave, it’s possible you might never get out.

Before you drown, that is.

Because this was a ghost river, and folks rarely – if ever- attempt to run it, there had been no warning sign at the top. There had been nothing at all, except a pool, and a very big drop.

“You know, I’m kind of glad we didn’t go over that”, Sharon said.

We looked around, and noticed two white trucks parked at the end of a dirt road that led to this point, and two men busily doing something near the base of the fall. Katy ran over to find out where we were.

“Yep”, she said after returning. “We missed our takeout, all right. Those guys said we’re about 8 miles below Holbrook”!

They were scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey, she said, taking sediment samples. And this was an irrigation dam built by the early residents of Joseph City, a tiny Mormon town nearby. ” They said they might be able to help us out when they’re finished, in a hour or so.”

That was good to hear, because we did need help. Our truck was 8 miles away, back in Holbrook, and we certainly didn’t fancy trying to carry our boats and gear that distance. Someone could hike back to get the camper, but there was no assurance it could safely navigate what looked to be a pretty rough road.

We decided to wait.

Two-and-one-half hours later, we loaded our boats, our gear, and ourselves into the back of a USGS pickup, and jounced our way back to Holbrook.

In Holbrook we duly transferred boats, gear, and people to our camper, and returned to the land of stone trees so that Dale and Katy could retrieve their van.

And then we drove home to the Grand Canyon.

* * * * *

We four had shared several adventures together before this, and we would share many more in the years to come. We would raft rivers like the Colorado, the Green, the Klamath, the Salt, and the Middle Fork of the Salmon, rivers that wound through incomparable wildness and had rapids that could swallow a boat in a second.

We would trek fourteen miles through remote, rugged country to reach Rainbow Bridge, and spend two months on a camper and van safari from the top of Mexico to the bottom, and then back, rafting a jungle river in the process.

And we would explore a cavern in the Grand Canyon that could only be reached by rappelling down a sheer cliff, and required two more rappels inside the cave, in utter darkness.

A cave that few had ever seen.

We would share that and more. And yet, in the years to come, whenever someone mentioned the Puerco, we would share something else.

A smile. A quiet, knowing smile. A smile that said we four had done something unique once. Something special.

We had run a ghost river.

If you enjoyed this story, consider clicking on the “Follow” button at the bottom of the page to receive notifications of future posts.

Great story, Randy! Thanks for sharing.

And for surviving!

Dave, the pleasure was mine….especially the surviving part!😊

An interesting adventure for sure. If you like this area you would love the Paris River Wilderness. The trailhead begins in Utah and it ends at Lee’s Ferry on the Colorado River. It is 35 miles long. You cross the creek, usually ankle deep, numerous times during the hike. You are given a map when you visit the trailhead lodge. This map shows where you can get fresh water and where you can camp. You camp where, if the river flashes floods, you will be safe. You all are the adventurous types and you will love it. A friend and I completed the hike in 5 days.

Sounds great, Lee. We once Buckskin Gulch, which is a very narrow slickrock Canyon that ends at the Pariah. Another nerve-wracking adventure….thunder was sounding while we were at the bottom of a death trap should it flash. That was Dale’s idea, too😊 LOVE the Escalante wilderness area!

Great Storyn. brought back some great memories. I’m glad you never told me that story before inviting us to join you on subsequent adventures. ..

After reflecting on that, it actually wouldn’t have mattered.

Ha ha! Well, I appreciate your trusting me with your life in Westwater Canyon. And if you hadn’t come, who would have told us about doodlebugs!

Thanks Randy! It brought back some memories of times and people I shared float trips and fun times with! How about some more?

Thanks, Forrest. Yes, there’ll definitely be more😊 And there sure were some fine memories crafted back then; I’ll never forget that great fall trip through Desolation Canyon back in ‘85, and learning “On The Loose” from your friend.

GREAT TIMES,GREAT FRIENDS!

Loved reading about your adventure Randy…you are a talented writer! I’ve only seen one moonbow in my life while driving at midnight through the Mt. Shasta Area in 1977. There was enough moisture in the atmosphere reflected by a full moon to create the phenomenon. It was amazing to see and I couldn’t get enough of it! Thanks for jogging my memory!

Thanks, Barb!😊 Moonbows are definitely memorable; I’ve never seen another!!!

whatsapp: +0079066111235

Hi, Randy— It looks like this blog has been inactive for a while, so I don’t know if you’ll see this, but I was searching for “Sharon Waltrip ranger Grand Canyon” and came across this post. I figured that, if she is still alive, I could share this through you.

I was reading an old travel journal from July 1985, when I was 16. My grandparents took me and my little sister to the Grand Canyon, and we encountered Sharon twice. She made quite an impression on me. Here’s what I wrote:

From July 16: “Had an evening at one of the museums and saw a slide show by a ranger. A young woman’s attempt to pound into our heads that we need wilderness—for its own sake. It worked for me—I have to act on this.”

From July 17: “Went on early morning walk at 6:30 along part of the rim trail. Had the same ranger as last night—Sharon Waltrip. Must commend her to the superintendent. We concentrate on using our other four senses more than sight—listening, tasting (piñon nuts and needles), smelling (ponderosa, sage brush, cliff roses), feeling (juniper bark). We also looked at the canyon upside down through our legs—it gives a whole new perspective.”

I just though that, if you could pass this on, she might be interested in knowing how much her work meant to a young girl.